- Acme Studios CEO Jonathan Harvey Interview

- The Lost Landscapes/Edward Allington

- Noko Yogo ‘GRANADA’ /Exhibition Review

- Naoko: her life in London/from the catalog GRANADA/Chris Roberts

- Naoko Yogo’s landscape photography/Tomohiro Nishimura(Art critic)

- Allotment statement

APRIL 2012

Acme Studios CEO Jonathan Harvey Interview

ALLOTMENT art project has Interviewed CEO of ACME studio Jonathan Harvey – the most influential artist studio organization in the UK. He told us about the 40 years experience and knowledge of organizing ACME studios and their future. We wanted to share his knowledge in making better studio environments in Japan.

ALLOTMENT art project has Interviewed CEO of ACME studio Jonathan Harvey – the most influential artist studio organization in the UK. He told us about the 40 years experience and knowledge of organizing ACME studios and their future. We wanted to share his knowledge in making better studio environments in Japan.

Read Jonathan Harvey Interview from here

Find more info on the Allotment project page

2011

The Lost Landscapes / Edward Allington

I remember it clearly now, but at the time it seemed unimportant. We had been talking to Naoko; it was the opening of a group show which included the works of her husband, the painter Masakatsu Kondo. We needed to leave, and she had so many more friends to talk to. We said goodbye, she turned and walked away, a slender, beautiful woman with great natural grace. It didn’t seem to matter, it was just one of those small everyday moments which are seemingly of no consequence. Then only a short time later she was gone – on her way to work on her bicycle, a left-turning truck, and she was lost, stolen from the world and from her work. Naoko Yogo was a very social artist. Her life was full of people – yet her work tends to be empty of their actual presence. The main body of her work is about landscape, shot in black and white using wet-process photography and a medium-format camera. Looking at her work, it is obvious that she had a very profound understanding of her medium: of the lens, of the camera, and the way the light would work on the film. Her first major body of work, the ‘Night Photographs’, show this clearly. There is a dense inner rigour in their composition. In one picture, a railway track curves from the left to the right of the image, at the centre of which is a pool of light. Small bushes are revealed growing in ground that looks incapable of sustaining life, and the only light – the light which made the photograph possible – comes from two electric lights. In another, we see a snow-bound street, a block-like building full of windows, the outlines of bushes, and a huge tree (trees are a common element in Naoko’s work). Again, all the light is artificial. These are extraordinary images, very carefully constructed. There are no people in the photographs because they were asleep in their houses. But Naoko was not: she was there in the darkness, capturing what little light there was in her camera. I have a copy of one of her black-and-white photographs from the ‘Night Photographs’ in front of me. All it shows is a barn – a place to shelter animals, or to keep essential tools to make food. It is the kind of building you might pass by without looking at. But the composition of the photograph makes you look: the light falling from the left of the image, the subtle outline of the trees in the background, the clear outline of the roof. In the foreground is another tree, leafless, almost hidden in the dense black of the photograph. There is snow on the ground. It is winter, the time when living is hardest. In the shadow cast by the roof are two small slits like eyes, and the door like a mouth only in so much as it is an entrance. There are no people in the photograph, but it is strangely like a portrait.

Naoko Yogo was a very social artist. Her life was full of people – yet her work tends to be empty of their actual presence. The main body of her work is about landscape, shot in black and white using wet-process photography and a medium-format camera. Looking at her work, it is obvious that she had a very profound understanding of her medium: of the lens, of the camera, and the way the light would work on the film. Her first major body of work, the ‘Night Photographs’, show this clearly. There is a dense inner rigour in their composition. In one picture, a railway track curves from the left to the right of the image, at the centre of which is a pool of light. Small bushes are revealed growing in ground that looks incapable of sustaining life, and the only light – the light which made the photograph possible – comes from two electric lights. In another, we see a snow-bound street, a block-like building full of windows, the outlines of bushes, and a huge tree (trees are a common element in Naoko’s work). Again, all the light is artificial. These are extraordinary images, very carefully constructed. There are no people in the photographs because they were asleep in their houses. But Naoko was not: she was there in the darkness, capturing what little light there was in her camera. I have a copy of one of her black-and-white photographs from the ‘Night Photographs’ in front of me. All it shows is a barn – a place to shelter animals, or to keep essential tools to make food. It is the kind of building you might pass by without looking at. But the composition of the photograph makes you look: the light falling from the left of the image, the subtle outline of the trees in the background, the clear outline of the roof. In the foreground is another tree, leafless, almost hidden in the dense black of the photograph. There is snow on the ground. It is winter, the time when living is hardest. In the shadow cast by the roof are two small slits like eyes, and the door like a mouth only in so much as it is an entrance. There are no people in the photograph, but it is strangely like a portrait. A house, a building, is an extension of ourselves. Its boundaries are representative of our boundaries. We live in a building in the same way as we live in our bodies. This one image from the ‘Night Photographs’ shows a humble place. It is a picture of our basic shelter, an image of the home, our security and its strength, our ability to offer hospitality, its walls our protection against the darkness and fear of the night when we sleep and are most vulnerable, our protection from death itself. The photograph, taken in darkness, shows not only Naoko’s lack of fear and belief in life, but also her deep knowledge of what shelter means to us. Naoko and Masakatsu’s house was, and still is known also as CCC (Clapham Community Centre), a seething hive of activity and hospitality where once Naoko was its hub; it is still driven by her spirit. In English the word window (in Japanese, mado) derives from the Icelandic windauge: ‘wind eye’, an aperture through which light and wind or air can enter the home. In the West we talk of the eyes as windows to the soul. Our word camera comes from the Latin for a chamber or a room, as in camera obscura, the precursor of the modern camera. In this seemingly simple photograph there is, to my mind, an image not of her, but of her life as an artist: a Japanese artist who, with her husband, had made her home in the West, who used that home to give shelter and hospitality, and who used her eyes and her mind. This small building is like a camera: there is the room inside, and the apertures which pierce its façade – its eyes – are like her eyes. This small building captured in the night is like the medium-format camera she carried with such care, which is our window into her inner world. If this small building sheltered humans, animals or even only their tools, then her camera sheltered those final rolls of film.

A house, a building, is an extension of ourselves. Its boundaries are representative of our boundaries. We live in a building in the same way as we live in our bodies. This one image from the ‘Night Photographs’ shows a humble place. It is a picture of our basic shelter, an image of the home, our security and its strength, our ability to offer hospitality, its walls our protection against the darkness and fear of the night when we sleep and are most vulnerable, our protection from death itself. The photograph, taken in darkness, shows not only Naoko’s lack of fear and belief in life, but also her deep knowledge of what shelter means to us. Naoko and Masakatsu’s house was, and still is known also as CCC (Clapham Community Centre), a seething hive of activity and hospitality where once Naoko was its hub; it is still driven by her spirit. In English the word window (in Japanese, mado) derives from the Icelandic windauge: ‘wind eye’, an aperture through which light and wind or air can enter the home. In the West we talk of the eyes as windows to the soul. Our word camera comes from the Latin for a chamber or a room, as in camera obscura, the precursor of the modern camera. In this seemingly simple photograph there is, to my mind, an image not of her, but of her life as an artist: a Japanese artist who, with her husband, had made her home in the West, who used that home to give shelter and hospitality, and who used her eyes and her mind. This small building is like a camera: there is the room inside, and the apertures which pierce its façade – its eyes – are like her eyes. This small building captured in the night is like the medium-format camera she carried with such care, which is our window into her inner world. If this small building sheltered humans, animals or even only their tools, then her camera sheltered those final rolls of film. Naoko Yogo trained as a sculptor at the Chelsea School of Art, and you can see this in the photographs. Sculpture and its form are revealed by light. I was taught as a sculptor to see the light cast upon a form as sculptural colour. You have to look at the form, you have to think about how the light would dance off the form. This is very clear in Naoko’s photographs: she looks at the landscape around her sculpturally. She has transformed this knowledge of making form into looking at form. Once having found her means of expression – the photograph and its machine, the camera – she travelled with it, looked through its lens and set its apertures. She worked in Bilbao, in Venezuela, in the Czech Republic and finally in Granada. This exhibition is an example of those final 40 rolls of film she shot there, negatives she never saw. Photographs showing huge expanses of seemingly uninhabited land. And again, as in the ‘Night Photographs’, these are places which seem as if they had never been looked at properly before. But as always there are trees, and through them, life; and through her brilliant use of light and darkness we can see the form as she saw it. In the ‘Night Photographs’ there was no light as such, but she found it. In the posthumous ‘Granada Photographs’ we see a landscape presumably almost obliterated by light; and within it she found the shadows. The medium-format camera is a very interesting instrument, and so is the film within it. Wet-process photography demands conceptual rigour, and in the digital age it is easy to forget just how unforgiving this medium is; to forget the blindness – for only the darkroom can reveal success or failure. The fact that she brought these images back unseen, and their evident success, is a testament to her command of the medium, her understanding of her chosen craft and her vision.a href=”http://mkondo.main.jp/allotment/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/4.jpg”>

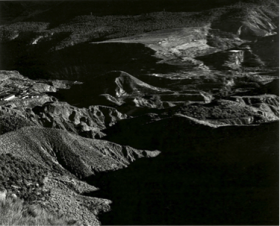

Naoko Yogo trained as a sculptor at the Chelsea School of Art, and you can see this in the photographs. Sculpture and its form are revealed by light. I was taught as a sculptor to see the light cast upon a form as sculptural colour. You have to look at the form, you have to think about how the light would dance off the form. This is very clear in Naoko’s photographs: she looks at the landscape around her sculpturally. She has transformed this knowledge of making form into looking at form. Once having found her means of expression – the photograph and its machine, the camera – she travelled with it, looked through its lens and set its apertures. She worked in Bilbao, in Venezuela, in the Czech Republic and finally in Granada. This exhibition is an example of those final 40 rolls of film she shot there, negatives she never saw. Photographs showing huge expanses of seemingly uninhabited land. And again, as in the ‘Night Photographs’, these are places which seem as if they had never been looked at properly before. But as always there are trees, and through them, life; and through her brilliant use of light and darkness we can see the form as she saw it. In the ‘Night Photographs’ there was no light as such, but she found it. In the posthumous ‘Granada Photographs’ we see a landscape presumably almost obliterated by light; and within it she found the shadows. The medium-format camera is a very interesting instrument, and so is the film within it. Wet-process photography demands conceptual rigour, and in the digital age it is easy to forget just how unforgiving this medium is; to forget the blindness – for only the darkroom can reveal success or failure. The fact that she brought these images back unseen, and their evident success, is a testament to her command of the medium, her understanding of her chosen craft and her vision.a href=”http://mkondo.main.jp/allotment/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/4.jpg”> The final series shot in Granada, some but not all shown posthumously in this exhibition, reveal an artist who had found her voice. Despite her loss, we can still see the world as she saw it through her camera. Or more accurately, as she wanted us to see it. In these works she brings us back to the notion of the sublime, where we can feel the fear of how small we are in the darkness, how small we are in the vastness of the landscape; but always she leaves some small clue as to how we do actually have a place and are part of it. How easy it is to take something away, how very difficult to make something new in the world. In her life, Naoko Yogo was able to bring people together. In her work, she was able to see and transform the extraordinary beauty of the world we live in. She was just emerging as an artist after two successful shows in Japan, and sadly she leaves only a small body of work. But there is no doubt that she saw and made something new, and nothing can steal that. Naoko’s eyes have gone from the world, but because of her courage, her humanity and her command of that simple but subtle machine we call the camera, the world as she saw it still exists; and what a world it is.

The final series shot in Granada, some but not all shown posthumously in this exhibition, reveal an artist who had found her voice. Despite her loss, we can still see the world as she saw it through her camera. Or more accurately, as she wanted us to see it. In these works she brings us back to the notion of the sublime, where we can feel the fear of how small we are in the darkness, how small we are in the vastness of the landscape; but always she leaves some small clue as to how we do actually have a place and are part of it. How easy it is to take something away, how very difficult to make something new in the world. In her life, Naoko Yogo was able to bring people together. In her work, she was able to see and transform the extraordinary beauty of the world we live in. She was just emerging as an artist after two successful shows in Japan, and sadly she leaves only a small body of work. But there is no doubt that she saw and made something new, and nothing can steal that. Naoko’s eyes have gone from the world, but because of her courage, her humanity and her command of that simple but subtle machine we call the camera, the world as she saw it still exists; and what a world it is.

Naoko Yogo ‘GRANADA’ Exhibition Review

Asahi Shimbun ’Vision of the Photography, link up’ Kalons Net ‘Naoko Yogo: Granada’ Hirouki Anzai ‘Granada’Naoko Yogo’s Exhibition’ Fogless ‘Special Interview 2009 – GRANADA’ HotShoe ‘Photo exhibition and book ‒ In Memory of artist Naoka Yogo’ Jotta ‘Naoko Yogo: Granada’

2009

Naoko: her life in London / from the catalog GRANADA

Chris Roberts (Author)

Naoko Kondo was born Naoko Yogo in Nagoya, Japan in 1971. She came to London in 1992 after gaining a Diploma in English and English Literature from Bunkyo University. Following a short course in photography, she completed her Foundation Studies at Camberwell College of Art before going on to study B.A. Fine Art at CCAD, where she specialized in sculpture. Naoko had always been drawn to the conceptual aspects of sculpture and from that became interested in architectural photography and pictures within sculptural objects. She fabricated precise and delicate forms that referenced architectural models as well as minimalist sculpture. When she moved away from the object towards photography, she continued to work with a cool detached eye, producing images of the urban landscape that were at once unsettling and matter-of –fact, investing the familiar and permanent with a sense of the transient or uncanny. This highly particular view of the urban (and later rural) landscape is to me one of the richest and most fascinating aspects of Naoko’s work. In 1993 she met the painter Masakatsu Kondo, who was coincidentally also from Nagoya, and had settled in London in 1988. He had just completed his studies at the Slade as she was embarking on her art education. They were married in 1998 and lived together in Brixton before moving in 2001 to Clapham to a house known affectionately amongst their friends as the Triple C (Clapham Community Centre). This was so called because it always seemed to be full of people cooking, eating, drinking, staying in the spare room, choosing tunes from Masakatsu’s formidable record collection, gossiping and just hanging out. Naoko, with her warm and vibrant personality, had a gift for bringing people together and putting them at their ease.

Naoko Kondo was born Naoko Yogo in Nagoya, Japan in 1971. She came to London in 1992 after gaining a Diploma in English and English Literature from Bunkyo University. Following a short course in photography, she completed her Foundation Studies at Camberwell College of Art before going on to study B.A. Fine Art at CCAD, where she specialized in sculpture. Naoko had always been drawn to the conceptual aspects of sculpture and from that became interested in architectural photography and pictures within sculptural objects. She fabricated precise and delicate forms that referenced architectural models as well as minimalist sculpture. When she moved away from the object towards photography, she continued to work with a cool detached eye, producing images of the urban landscape that were at once unsettling and matter-of –fact, investing the familiar and permanent with a sense of the transient or uncanny. This highly particular view of the urban (and later rural) landscape is to me one of the richest and most fascinating aspects of Naoko’s work. In 1993 she met the painter Masakatsu Kondo, who was coincidentally also from Nagoya, and had settled in London in 1988. He had just completed his studies at the Slade as she was embarking on her art education. They were married in 1998 and lived together in Brixton before moving in 2001 to Clapham to a house known affectionately amongst their friends as the Triple C (Clapham Community Centre). This was so called because it always seemed to be full of people cooking, eating, drinking, staying in the spare room, choosing tunes from Masakatsu’s formidable record collection, gossiping and just hanging out. Naoko, with her warm and vibrant personality, had a gift for bringing people together and putting them at their ease. After graduating from Chelsea in 1998, Naoko struggled to find a focus or style for her practice. In 2002 she met the artist Taiji Matue who, like herself, had come to photography by an unusual route, in his case a scientific background working with telescopes. He had an unparalleled grasp of the technology and techniques of photography and he stressed how vital this was – without command and understanding of the total process one could never fully understand either the possibilities of the medium or one’s own ideas. This was a revelation to Naoko who began to fully explore, with another South London photographer Robert Hackman, the mechanics of photography and take extra pains in her craft. This meant others taking extra pains too as the larger images took up to twenty minutes to print and her darkroom was upstairs in the rather rickety Triple C. The slightest movement in the house would ruin the process and this meant everyone (including Masakatsu) staying perfectly still. Around this time, Naoko began a series of night photographs, one of which appeared in my book about London’s bridges (Cross River Traffic Granta 2005) (1). The brief was to create an image of each crossing that might not be instantly recognizable but which would disclose some hidden aspect of that bridge’s atmosphere or history. Naoko’s image of Hungerford Bridge (now Jubilee Bridges) fits this brief perfectly. The bright, airy, 21st century structure appears haunted by the darkness and danger of the iron footbridge that had previously hung parasitically from the railway line. As in many of her night photographs, water and shadow are imbued with a rich texture and eerie depth that makes them seem solid. There is almost a sense of a crossing beneath the crossing.

After graduating from Chelsea in 1998, Naoko struggled to find a focus or style for her practice. In 2002 she met the artist Taiji Matue who, like herself, had come to photography by an unusual route, in his case a scientific background working with telescopes. He had an unparalleled grasp of the technology and techniques of photography and he stressed how vital this was – without command and understanding of the total process one could never fully understand either the possibilities of the medium or one’s own ideas. This was a revelation to Naoko who began to fully explore, with another South London photographer Robert Hackman, the mechanics of photography and take extra pains in her craft. This meant others taking extra pains too as the larger images took up to twenty minutes to print and her darkroom was upstairs in the rather rickety Triple C. The slightest movement in the house would ruin the process and this meant everyone (including Masakatsu) staying perfectly still. Around this time, Naoko began a series of night photographs, one of which appeared in my book about London’s bridges (Cross River Traffic Granta 2005) (1). The brief was to create an image of each crossing that might not be instantly recognizable but which would disclose some hidden aspect of that bridge’s atmosphere or history. Naoko’s image of Hungerford Bridge (now Jubilee Bridges) fits this brief perfectly. The bright, airy, 21st century structure appears haunted by the darkness and danger of the iron footbridge that had previously hung parasitically from the railway line. As in many of her night photographs, water and shadow are imbued with a rich texture and eerie depth that makes them seem solid. There is almost a sense of a crossing beneath the crossing. The night photographs required a strict routine. Naoko would head off on her bicycle after dark to set up her tripod by the river or in Battersea Park (2). The following day she would begin the work of developing and making test strips and prints, often rejecting many prints before arriving at one which satisfied her. She continued to refine her technique on a trip to the Czech Republic in 2005(3.4), creating images in which the camera stands as witness to the loneliness and strangeness of the night world, with all its danger, mystery and attraction. Although she had by now been offered two solo exhibitions in Japan, both of which took place in the summer of 2005 and proved highly successful, Naoko was still shy about her work. It was many months before she was ready to show the perfected photographs even to Masakatsu or her closest friends. It is interesting to reflect on the relationship between Masakatsu’s and Naoko’s individual practices. Both artists chose landscape as their subject matter early on, and both seem to use this subject matter as a means of exploring places that are “other”, dreamlike, hallucinatory, or steeped in memory. Unlike some artist couples, their practices were and are complementary rather than competitive, yet each also retain a strong individual identity in their work, with Masakatsu transforming his subject through the use of scintillating, hallucinatory colour, whilst Naoko chose to work exclusively in monochrome after leaving college, investing her images with a dreamlike quality through her use of long exposure and the creation of rich textures via the printing process. Interestingly, shortly before her death Naoko had become interested in working with colour, setting up a meeting to discuss this with the Photo Fusion Collective in Brixton and this would have undoubtedly represented a major and exciting development in her work.

The night photographs required a strict routine. Naoko would head off on her bicycle after dark to set up her tripod by the river or in Battersea Park (2). The following day she would begin the work of developing and making test strips and prints, often rejecting many prints before arriving at one which satisfied her. She continued to refine her technique on a trip to the Czech Republic in 2005(3.4), creating images in which the camera stands as witness to the loneliness and strangeness of the night world, with all its danger, mystery and attraction. Although she had by now been offered two solo exhibitions in Japan, both of which took place in the summer of 2005 and proved highly successful, Naoko was still shy about her work. It was many months before she was ready to show the perfected photographs even to Masakatsu or her closest friends. It is interesting to reflect on the relationship between Masakatsu’s and Naoko’s individual practices. Both artists chose landscape as their subject matter early on, and both seem to use this subject matter as a means of exploring places that are “other”, dreamlike, hallucinatory, or steeped in memory. Unlike some artist couples, their practices were and are complementary rather than competitive, yet each also retain a strong individual identity in their work, with Masakatsu transforming his subject through the use of scintillating, hallucinatory colour, whilst Naoko chose to work exclusively in monochrome after leaving college, investing her images with a dreamlike quality through her use of long exposure and the creation of rich textures via the printing process. Interestingly, shortly before her death Naoko had become interested in working with colour, setting up a meeting to discuss this with the Photo Fusion Collective in Brixton and this would have undoubtedly represented a major and exciting development in her work. Naoko loved to travel alone with her camera. She visited Venezuela in 2002 and came back with a huge smile and a suntan that made her look curiously Latin American. Shortly before her death, she spent a week criss-crossing the Sierra Nevada between Grenada and the coast, shooting over forty reels of film. The sixteen images in this exhibition and catalogue have been selected from these films by Masakatsu and a group of Naoko’s friends. The large, highly detailed landscapes clearly demonstrate her growing prowess as a photographer. Looking at the contact sheets from this trip, one gets a sense of Naoko working with a great confidence and sense of freedom, experimenting, enjoying herself and taking risks. The images are diverse, sometimes imposing a definite, almost classical composition onto the landscape, and at other times focusing on a texture or detail. Although very different in atmosphere from her earlier work, these images also play on the relation between the observed landscape and the landscape of the mind. There is a sense of curiosity, of enquiry – as in the night photographs, each image is as much about what we cannot see as what we can, about what is round the corner beyond that odd, isolated gate. Naoko uses the camera as an intermediary between the eye and the imagination, and the resulting works are exquisite, vibrant and poetic. Her work was beginning to take a weight of its own and finally gaining greater recognition in the art world. Naoko’s love of landscape and sense of place was not confined to her photographic work. She worked briefly as a gardener and acquired that most English of things, an allotment. Out of the many stories her friends remember her by this one always sticks in my mind. There were no taps on the allotment so she had to carry water there herself. During the summer she would cycle the 3 miles from Clapham to Tooting with a rucksack full of bottled water, no mean feat in the baking sun. She had worked out the bare minimum each plant required, no more than a glassful each, and was able to carry just enough to keep her precious vegetables alive. For most people this would be a ridiculously arduous task, but Naoko didn’t see it like that. For her it was just a small habitual act of kindness that would result in something coming to fruition, and that for me sums up how Naoko lived her life.

Naoko loved to travel alone with her camera. She visited Venezuela in 2002 and came back with a huge smile and a suntan that made her look curiously Latin American. Shortly before her death, she spent a week criss-crossing the Sierra Nevada between Grenada and the coast, shooting over forty reels of film. The sixteen images in this exhibition and catalogue have been selected from these films by Masakatsu and a group of Naoko’s friends. The large, highly detailed landscapes clearly demonstrate her growing prowess as a photographer. Looking at the contact sheets from this trip, one gets a sense of Naoko working with a great confidence and sense of freedom, experimenting, enjoying herself and taking risks. The images are diverse, sometimes imposing a definite, almost classical composition onto the landscape, and at other times focusing on a texture or detail. Although very different in atmosphere from her earlier work, these images also play on the relation between the observed landscape and the landscape of the mind. There is a sense of curiosity, of enquiry – as in the night photographs, each image is as much about what we cannot see as what we can, about what is round the corner beyond that odd, isolated gate. Naoko uses the camera as an intermediary between the eye and the imagination, and the resulting works are exquisite, vibrant and poetic. Her work was beginning to take a weight of its own and finally gaining greater recognition in the art world. Naoko’s love of landscape and sense of place was not confined to her photographic work. She worked briefly as a gardener and acquired that most English of things, an allotment. Out of the many stories her friends remember her by this one always sticks in my mind. There were no taps on the allotment so she had to carry water there herself. During the summer she would cycle the 3 miles from Clapham to Tooting with a rucksack full of bottled water, no mean feat in the baking sun. She had worked out the bare minimum each plant required, no more than a glassful each, and was able to carry just enough to keep her precious vegetables alive. For most people this would be a ridiculously arduous task, but Naoko didn’t see it like that. For her it was just a small habitual act of kindness that would result in something coming to fruition, and that for me sums up how Naoko lived her life.

2009

Naoko Yogo’s landscape photography / from the catalog GRANADA

Tomohiro Nishimura (Art critic)

Granada is Naoko Yogo’s first published collection of photographs but it has also become her posthumous collection. Just as Yogo was starting to engage intensively in her photographic work, a tragic accident cut short her creative activities. Granada was printed from film that Yogo left behind and shows the unique worldview that she achieved as a photographer. There were many twists and turns along the way before Yogo established her own style. In 1992 she moved to the UK where she learnt basic monochrome photography at LOFC’s Photography and Pre-foundation course. Although she was interested in photography and film at the time, her fascination with fine art grew and in 1995 she began to study modern sculpture at Chelsea College of Art and Design. Even while she was studying sculpture, Yogo maintained her interest in photography and, indeed, she exhibited her photographs in her final show at Chelsea College. The pieces comprised three images of the scenery outside, each taken from inside a room, framed by a window. Even after her graduation, Yogo still took photographs. She did not exhibit but continued to experiment for a while as she sought her own style. It was around 2003 that she came to embrace photography seriously, influenced by seeing exhibitions by photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, and also by her contact with other photographers such as Tomoko Yoneda and Taiji Matsue. Looking at images made by past masters and meeting practicing photographers seems to have deepened her knowledge of photography. She became aware of the importance of the technical aspects of photography and began to explore and study it independently, defining her style in the process.

There were many twists and turns along the way before Yogo established her own style. In 1992 she moved to the UK where she learnt basic monochrome photography at LOFC’s Photography and Pre-foundation course. Although she was interested in photography and film at the time, her fascination with fine art grew and in 1995 she began to study modern sculpture at Chelsea College of Art and Design. Even while she was studying sculpture, Yogo maintained her interest in photography and, indeed, she exhibited her photographs in her final show at Chelsea College. The pieces comprised three images of the scenery outside, each taken from inside a room, framed by a window. Even after her graduation, Yogo still took photographs. She did not exhibit but continued to experiment for a while as she sought her own style. It was around 2003 that she came to embrace photography seriously, influenced by seeing exhibitions by photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, and also by her contact with other photographers such as Tomoko Yoneda and Taiji Matsue. Looking at images made by past masters and meeting practicing photographers seems to have deepened her knowledge of photography. She became aware of the importance of the technical aspects of photography and began to explore and study it independently, defining her style in the process. From 2004 to early 2005, Yogo took photographs of night scenery in London and the Czech Republic. These images were exhibited in 2005 in Suikatou, Tokyo and Gallery Tatsuya, Nagoya in what were to be her first – and last – solo exhibitions in Japan. By this stage Yogo had established her own style; she had a firm idea about how to capture what she wanted, and the quality of finish on the print had improved. In November 2005 Yogo travelled to Spain to take photographs. The images from this period are the Granada series that form this collection. Although they were an extension of the previous year’s Night series, they moved closer to landscape photography and a development of her artistic expression can be observed. Sadly this series was not exhibited during Yogo’s lifetime. The images that clearly demonstrate Yogo’s style are the Night series exhibited in the summer of 2005 and the Granada images taken in November 2005 and I would like to say something about her photography in reference to these two series. Yogo’s photography had a very clear style; black and white landscape images always taken from a distance and rarely featuring people. By thinking through her style dispassionately she made explicit things that were essential to her. Her interest in landscape developed before she started photography seriously. When she participated in an open air sculpture exhibition in 1995, she attached landscape photographs to sections of her three-dimensional piece. At this time she was using photographs as a way of exploring the relationship between reality and images. This was an unusual approach but was consistent with her interest in landscape.

From 2004 to early 2005, Yogo took photographs of night scenery in London and the Czech Republic. These images were exhibited in 2005 in Suikatou, Tokyo and Gallery Tatsuya, Nagoya in what were to be her first – and last – solo exhibitions in Japan. By this stage Yogo had established her own style; she had a firm idea about how to capture what she wanted, and the quality of finish on the print had improved. In November 2005 Yogo travelled to Spain to take photographs. The images from this period are the Granada series that form this collection. Although they were an extension of the previous year’s Night series, they moved closer to landscape photography and a development of her artistic expression can be observed. Sadly this series was not exhibited during Yogo’s lifetime. The images that clearly demonstrate Yogo’s style are the Night series exhibited in the summer of 2005 and the Granada images taken in November 2005 and I would like to say something about her photography in reference to these two series. Yogo’s photography had a very clear style; black and white landscape images always taken from a distance and rarely featuring people. By thinking through her style dispassionately she made explicit things that were essential to her. Her interest in landscape developed before she started photography seriously. When she participated in an open air sculpture exhibition in 1995, she attached landscape photographs to sections of her three-dimensional piece. At this time she was using photographs as a way of exploring the relationship between reality and images. This was an unusual approach but was consistent with her interest in landscape. Yogo travelled frequently. For her, a photography trip meant encountering landscapes. She enjoyed travelling in South America and Spain, often choosing to visit rural areas. She did not merely take photographs as she travelled around; the purpose of the trip was photography itself. And in travelling alone to unfamiliar regions, it seems that she was somehow also seeking solitude for herself. Travelling to unfamiliar places allowed her to escape from the daily routine for a time. The desire to distance herself from daily life allowed her to become more aware of herself and concentrate on the photography. At the same time, it was an opportunity for introspection. Each photography trip was a journey to find landscape subjects for her images but also a journey inside herself. Yogo would walk around unfamiliar regions and, if she came across some scenery that caught her attention, she would capture it. For her, it was important to encounter the unknown; the raw emotions and wonder at the scenery were the motivation for pressing the shutter. In that sense, her works could be seen as conventional landscape snaps. However, these images were more than just a record of the landscape. The landscapes that she captured also reflected something of her inner world. They were real landscapes while at the same time showing the landscape of her psyche. What is unique about Yogo’s photographs is the way she distanced herself from the landscape. She did not generally come close to the subject or take close-up images. The images taken in Granada tend strongly towards the abstract, and a number of them have a very ambiguous sense of scale. But these images seem to have been taken from quite a distance.

Yogo travelled frequently. For her, a photography trip meant encountering landscapes. She enjoyed travelling in South America and Spain, often choosing to visit rural areas. She did not merely take photographs as she travelled around; the purpose of the trip was photography itself. And in travelling alone to unfamiliar regions, it seems that she was somehow also seeking solitude for herself. Travelling to unfamiliar places allowed her to escape from the daily routine for a time. The desire to distance herself from daily life allowed her to become more aware of herself and concentrate on the photography. At the same time, it was an opportunity for introspection. Each photography trip was a journey to find landscape subjects for her images but also a journey inside herself. Yogo would walk around unfamiliar regions and, if she came across some scenery that caught her attention, she would capture it. For her, it was important to encounter the unknown; the raw emotions and wonder at the scenery were the motivation for pressing the shutter. In that sense, her works could be seen as conventional landscape snaps. However, these images were more than just a record of the landscape. The landscapes that she captured also reflected something of her inner world. They were real landscapes while at the same time showing the landscape of her psyche. What is unique about Yogo’s photographs is the way she distanced herself from the landscape. She did not generally come close to the subject or take close-up images. The images taken in Granada tend strongly towards the abstract, and a number of them have a very ambiguous sense of scale. But these images seem to have been taken from quite a distance. In some ways, it seems that Yogo did not want to encroach on the world that is the subject of the images. In short, she did not want to affect the landscape by her presence. In this sense, she tried to capture the scenery as it was. By doing this, perhaps she was allowing a distance to form between herself and the landscape. However, perhaps the detachment from the landscape was necessary for her introspection. For Yogo, encountering the landscape was encountering herself. To put it another way, objectifying the landscape was a way of objectifying herself. It is possible that maintaining detachment from the landscape and looking from a distance were a way of looking into her own psyche. Another interesting aspect of Yogo’s photographs is the composition of the landscapes. In particular, the composition of the Granada images is quite distinct, and she creates a unique viewpoint. Perhaps her consciousness is being reflected here, too. In the Night series, some of the images were composed like paintings. This was clearly a product of the design sensibilities that she learnt at art school. But this does not mean that the images were made with design as their intent. Although the end result may be a picture-like composition, it can be said that the images are a manifestation of her way of seeing the landscape. Yogo’s images have a sense of desertion, an impression of loneliness. This is striking in the Night series but can be seen even more strongly in the images taken in Granada. Yogo had an extremely cheerful personality; she was a very outgoing woman who made friends easily with anyone, so there seems to be some discrepancy between her images and the person she was, which is very interesting when considering her photographs. According to Masakatsu Kondo, her husband, she was a solitary person and her landscape photographs reveal a deep layer of her consciousness that was normally kept hidden. Another aspect of Yogo’s photographs that is interesting is the appearance of darkness and shadows. The Night series was, of course, taken at night and so naturally there are many dark areas. In all those photographs, light shines on part of the image but most of it is shrouded in darkness. It seems that she was photographing not only the scene but the darkness itself, as if she had some kind of affinity with darkness. The Granada photographs were taken in daylight so, unlike the Night series, darkness is not the main theme. However one of the features of these images is the shadows and the sections that appear black; it seems that she was seeking out landscapes that incorporated such features. Clearly, places shrouded in shadow and darkness appealed to her as a reflection of the depths of her mind. Yogo’s photographs document not only her encounters with scenery but also herself as the viewer. They are a record of the landscape and at the same time a record of herself. Even though she does not appear in the images, she is undeniably present. Yogo is no longer in this world but you can meet her through her photographs. These landscape photographs are her legacy to us.

In some ways, it seems that Yogo did not want to encroach on the world that is the subject of the images. In short, she did not want to affect the landscape by her presence. In this sense, she tried to capture the scenery as it was. By doing this, perhaps she was allowing a distance to form between herself and the landscape. However, perhaps the detachment from the landscape was necessary for her introspection. For Yogo, encountering the landscape was encountering herself. To put it another way, objectifying the landscape was a way of objectifying herself. It is possible that maintaining detachment from the landscape and looking from a distance were a way of looking into her own psyche. Another interesting aspect of Yogo’s photographs is the composition of the landscapes. In particular, the composition of the Granada images is quite distinct, and she creates a unique viewpoint. Perhaps her consciousness is being reflected here, too. In the Night series, some of the images were composed like paintings. This was clearly a product of the design sensibilities that she learnt at art school. But this does not mean that the images were made with design as their intent. Although the end result may be a picture-like composition, it can be said that the images are a manifestation of her way of seeing the landscape. Yogo’s images have a sense of desertion, an impression of loneliness. This is striking in the Night series but can be seen even more strongly in the images taken in Granada. Yogo had an extremely cheerful personality; she was a very outgoing woman who made friends easily with anyone, so there seems to be some discrepancy between her images and the person she was, which is very interesting when considering her photographs. According to Masakatsu Kondo, her husband, she was a solitary person and her landscape photographs reveal a deep layer of her consciousness that was normally kept hidden. Another aspect of Yogo’s photographs that is interesting is the appearance of darkness and shadows. The Night series was, of course, taken at night and so naturally there are many dark areas. In all those photographs, light shines on part of the image but most of it is shrouded in darkness. It seems that she was photographing not only the scene but the darkness itself, as if she had some kind of affinity with darkness. The Granada photographs were taken in daylight so, unlike the Night series, darkness is not the main theme. However one of the features of these images is the shadows and the sections that appear black; it seems that she was seeking out landscapes that incorporated such features. Clearly, places shrouded in shadow and darkness appealed to her as a reflection of the depths of her mind. Yogo’s photographs document not only her encounters with scenery but also herself as the viewer. They are a record of the landscape and at the same time a record of herself. Even though she does not appear in the images, she is undeniably present. Yogo is no longer in this world but you can meet her through her photographs. These landscape photographs are her legacy to us.

Allotment statement

“Allotment” is a travel award established in 2009 to commemorate the life and work of artist Naoko Yogo. The Allotment award provides opportunities for young Japanese artists to travel, with the aim of enhancing their experience, broadening their knowledge and vision, and developing and nurturing their work. Before Naoko passed away in 2005, she devoted a lot of time and energy to her allotment in South London. It was an important part of her life, a source of great joy as well as hard work. In his text for Naoko’s book, Chris Roberts recalls one of her stories about her allotment: “There were no taps on the allotment so she had to carry water there herself. She had worked out the bare minimum each plant required, no more than a glassful each, it was just a small habitual act of kindness that would result in something coming to fruition.” For Naoko, there was no difference between working on her art and on her allotment: they coexisted as vital parts of her life. In both, she worked with enthusiasm and care, paying attention to small details. Though each required a great deal of patience, she never compromised. She went through a constant process of trial and error in order to accomplish what she set out to do. The Allotment travel award will reflect Naoko’s life and legacy by supporting artists who, like her, are guided by a passion to produce their work and yet endeavour to pursue their dreams. All proceeds from the sales of Naoko’s book and photographs will be donated to the Allotment fund.